What are the symptoms of a heart attack?

What are the symptoms of a heart attack?

Although chest pain or pressure is the most common symptom of a heart attack, heart attack victims may experience a variety of symptoms including:

- Pain, fullness, and/or squeezing sensation of the chest

- Jaw pain, toothache, headache

- Shortness of breath

- Nausea, vomiting , and/or general epigastric (upper middle abdomen) discomfort

- Sweating

- Heartburn and/or indigestion

- Arm pain (more commonly the left arm, but may be either arm)

- Upper back pain

- General malaise (vague feeling of illness)

- No symptoms (Approximately one quarter of all heart attacks are silent, without chest pain or new symptoms. Silent heart attacks are especially common among patients with diabetes mellitus.)

Even though the symptoms of a heart attack at times can be vague and mild, it is important to remember that heart attacks producing no symptoms or only mild symptoms can be just as serious and life-threatening as heart attacks that cause severe chest pain. Too often patients attribute heart attack symptoms to "indigestion," "fatigue," or "stress," and consequently delay seeking prompt medical attention. One cannot overemphasize the importance of seeking prompt medical attention in the presence of symptoms that suggest a heart attack. Early diagnosis and treatment saves lives, and delays in reaching medical assistance can be fatal. A delay in treatment can lead to permanently reduced function of the heart due to more extensive damage to the heart muscle. Death also may occur as a result of the sudden onset of arrhythmias such as ventricular fibrillation.

What causes a heart attack?

What causes a heart attack?

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a gradual process by which plaques (collections) of cholesterol are deposited in the walls of arteries. Cholesterol plaques cause hardening of the arterial walls and narrowing of the inner channel (lumen) of the artery. Arteries that are narrowed by atherosclerosis cannot deliver enough blood to maintain normal function of the parts of the body they supply. For example, atherosclerosis of the arteries in the legs causes reduced blood flow to the legs. Reduced blood flow to the legs can lead to pain in the legs while walking or exercising, leg ulcers, or a delay in the healing of wounds to the legs. Atherosclerosis of the arteries that furnish blood to the brain can lead to vascular dementia (mental deterioration due to gradual death of brain tissue over many years) or stroke (sudden death of brain tissue).

In many people, atherosclerosis can remain silent (causing no symptoms or health problems) for years or decades. Atherosclerosis can begin as early as the teenage years, but symptoms or health problems usually do not arise until later in adulthood when the arterial narrowing becomes severe. Smoking cigarettes, high blood pressure, elevated cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus can accelerate atherosclerosis and lead to the earlier onset of symptoms and complications, particularly in those people who have a family history of early atherosclerosis.

Coronary atherosclerosis (or coronary artery disease) refers to the atherosclerosis that causes hardening and narrowing of the coronary arteries. Diseases caused by the reduced blood supply to the heart muscle from coronary atherosclerosis are called coronary heart diseases (CHD). Coronary heart diseases include heart attacks, sudden unexpected death, chest pain (angina), abnormal heart rhythms, and heart failure due to weakening of the heart muscle.

Atherosclerosis and angina pectoris

Angina pectoris (also referred to as angina) is chest pain or pressure that occurs when the blood and oxygen supply to the heart muscle cannot keep up with the needs of the muscle. When coronary arteries are narrowed by more than 50 to 70 percent, the arteries may not be able to increase the supply of blood to the heart muscle during exercise or other periods of high demand for oxygen. An insufficient supply of oxygen to the heart muscle causes angina. Angina that occurs with exercise or exertion is called exertional angina. In some patients, especially diabetics, the progressive decrease in blood flow to the heart may occur without any pain or with just shortness of breath or unusually early fatigue.

Exertional angina usually feels like a pressure, heaviness, squeezing, or aching across the chest. This pain may travel to the neck, jaw, arms, back, or even the teeth, and may be accompanied by shortness of breath, nausea, or a cold sweat. Exertional angina typically lasts from one to 15 minutes and is relieved by rest or by taking nitroglycerin by placing a tablet under the tongue. Both resting and nitroglycerin decrease the heart muscle's demand for oxygen, thus relieving angina. Exertional angina may be the first warning sign of advanced coronary artery disease. Chest pains that just last a few seconds rarely are due to coronary artery disease.

Angina also can occur at rest. Angina at rest more commonly indicates that a coronary artery has narrowed to such a critical degree that the heart is not receiving enough oxygen even at rest. Angina at rest infrequently may be due to spasm of a coronary artery (a condition called Prinzmetal's or variant angina). Unlike a heart attack, there is no permanent muscle damage with either exertional or rest angina.

Atherosclerosis and heart attack

Occasionally the surface of a cholesterol plaque in a coronary artery may rupture, and a blood clot forms on the surface of the plaque. The clot blocks the flow of blood through the artery and results in a heart attack (see picture below). The cause of rupture that leads to the formation of a clot is largely unknown, but contributing factors may include cigarette smoking or other nicotine exposure, elevated LDL cholesterol, elevated levels of blood catecholamines (adrenaline), high blood pressure, and other mechanical and biochemical forces.

Unlike exertional or rest angina, heart muscle dies during a heart attack and loss of the muscle is permanent, unless blood flow can be promptly restored, usually within one to six hours.

While heart attacks can occur at any time, more heart attacks occur between 4:00 A.M. and 10:00 A.M. because of the higher blood levels of adrenaline released from the adrenal glands during the morning hours. Increased adrenaline, as previously discussed, may contribute to rupture of cholesterol plaques.

Approximately 50% of patients who develop heart attacks have warning symptoms such as exertional angina or rest angina prior to their heart attacks, but these symptoms may be mild and discounted.

What is a heart attack?

What is a heart attack?

A heart attack (also known as a myocardial infarction) is the death of heart muscle from the sudden blockage of a coronary artery by a blood clot. Coronary arteries are blood vessels that supply the heart muscle with blood and oxygen. Blockage of a coronary artery deprives the heart muscle of blood and oxygen,causing injury to the heart muscle. Injury to the heart muscle causes chest pain and chest pressure sensation. If blood flow is not restored to the heart muscle within 20 to 40 minutes, irreversible death of the heart muscle will begin to occur. Muscle continues to die for six to eight hours at which time the heart attack usually is "complete." The dead heart muscle is eventually replaced by scar tissue.

Approximately one million Americans suffer a heart attack each year. Four hundred thousand of them die as a result of their heart attack.

Borderline high blood pressure

Borderline high blood pressure

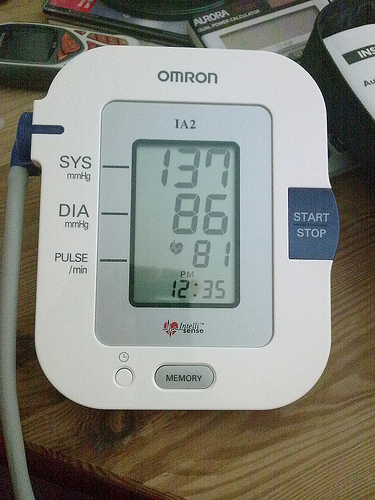

Borderline hypertension is defined as mildly elevated blood pressure higher than 140/90 mm Hg at some times, and lower than that at other times. As in the case of white coat hypertension, patients with borderline hypertension need to have their blood pressure taken on several occasions and their end-organ damage assessed in order to establish whether their hypertension is significant.

People with borderline hypertension may have a tendency as they get older to develop more sustained or higher elevations of blood pressure. They have a modestly increased risk of developing heart-related (cardiovascular) disease. Therefore, even if the hypertension does not appear to be significant initially, people with borderline hypertension should have continuing follow-up of their blood pressure and monitoring for the complications of hypertension.

If, during the follow-up of a patient with borderline hypertension, the blood pressure becomes persistently higher than 140/ 90 mm Hg, an anti-hypertensive medication is usually started. Even if the diastolic pressure remains at a borderline level (usually under 90 mm Hg, yet persistently above 85) treatment may be started in certain circumstances.

White coat high blood pressure

A single elevated blood pressure reading in the doctor's office can be misleading because the elevation may be only temporary. It may be caused by a patient's anxiety related to the stress of the examination and fear that something will be wrong with his or her health. The initial visit to the physician's office is often the cause of an artificially high blood pressure that may disappear with repeated testing after rest and with follow-up visits and blood pressure checks. One out of four people that are thought to have mild hypertension actually may have normal blood pressure when they are outside the physician's office. An increase in blood pressure noted only in the doctor's office is called 'white coat hypertension.' The name suggests that the physician's white coat induces the patient's anxiety and a brief increase in blood pressure. A diagnosis of white coat hypertension might imply that it is not a clinically important or dangerous finding.

However, caution is warranted in assessing white coat hypertension. An elevated blood pressure brought on by the stress and anxiety of a visit to the doctor may not necessarily always be a harmless finding since other stresses in a patient's life may also cause elevations in the blood pressure that are not ordinarily being measured. Monitoring blood pressure at home by blood pressure cuff or continuous monitoring equipment or at a pharmacy can help estimate the frequency and consistency of higher blood pressure readings. Additionally, conducting appropriate tests to search for any complications of hypertension can help evaluate the significance of variable blood pressure readings.

Isolated systolic high blood pressure

Isolated systolic high blood pressure

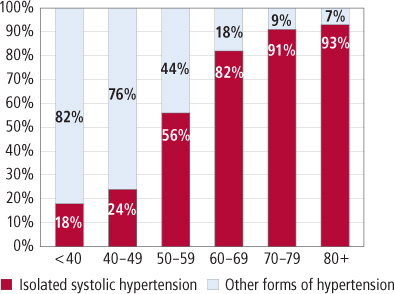

Remember that the systolic blood pressure is the top number in the blood pressure reading and represents the pressure in the arteries as the heart contracts and pumps blood into the arteries. A systolic blood pressure that is persistently higher than 140 mm Hg is usually considered elevated, especially when associated with an elevated diastolic pressure (over 90).

Isolated systolic hypertension, however, is defined as a systolic pressure that is above 140 mm Hg with a diastolic pressure that still is below 90. This disorder primarily affects older people and is characterized by an increased (wide) pulse pressure. The pulse pressure is the difference between the systolic and diastolic blood pressures. An elevation of the systolic pressure without an elevation of the diastolic pressure, as in isolated systolic hypertension, therefore, increases the pulse pressure. Stiffening of the arteries contributes to this widening of the pulse pressure.

Once considered to be harmless, a high pulse pressure is now considered an important precursor or indicator of health problems and potential end-organ damage. Isolated systolic hypertension is associated with a two to four times increased future risk of an enlarged heart, a heart attack

(myocardial infarction), a stroke (brain damage), and death from heart disease or a stroke. Clinical studies in patients with isolated systolic hypertension have indicated that a reduction in systolic blood pressure by at least 20 mm to a level below 160 mm Hg reduces these increased risks.

How is high blood pressure defined?

How is high blood pressure defined?

Blood pressure can be affected by several factors, so it is important to standardize the environment when blood pressure is measured. For at least one hour before blood pressure is taken, avoid eating, strenuous exercise (which can lower blood pressure), smoking, and caffeine intake

. Other stresses may alter the blood pressure and need to be considered when blood pressure is measured.

Even though most insurance companies consider high blood pressure to be 140/90 and higher for the general population, these levels may not be appropriate cut-offs for all individuals. Many experts in the field of hypertension view blood pressure levels as a range, from lower levels to higher levels. Such a range implies there are no clear or precise cut-off values to separate normal blood pressure from high blood pressure. Individuals with so-called pre-hypertension (defined as a blood pressure between 120/80 and 139/89) may benefit from lowering of blood pressure by life style modification and possibly medication especially if there are other risk factors for end-organ damage such as diabetes or kidney disease (life style changes are discussed below).

For some people, blood pressure readings lower than 140/90 may be a more appropriate normal cut-off level. For example, in certain situations, such as in patients with long duration (chronic) kidney diseases that spill (lose) protein into the urine (proteinuria), the blood pressure is ideally kept at 130/80, or even lower. The purpose of reducing the blood pressure to this level in these patients is to slow the progression of kidney damage. Patients with diabetes (diabetes mellitus) may also benefit from blood pressure that is maintained at a level lower than 130/80. In addition, African Americans, who have an increased risk for developing the complications of hypertension, may decrease this risk by reducing their systolic blood pressure to less than 135 and the diastolic blood pressure to 80 mm Hg or less.

In line with the thinking that the risk of end-organ damage from high blood pressure represents a continuum, statistical analysis reveals that beginning at a blood pressure of 115/75 the risk of cardiovascular disease doubles with each increase in blood pressure of 20/10. This type of analysis has led to an ongoing "rethinking" in regard to who should be treated for hypertension, and what the goals of treatment should be.

How is the blood pressure measured?

How is the blood pressure measured?

The blood pressure usually is measured with a small, portable instrument called a blood pressure cuff (sphygmomanometer). (Sphygmo is Greek for pulse, and a manometer measures pressure.) The blood pressure cuff consists of an air pump, a pressure gauge, and a rubber cuff. The instrument measures the blood pressure in units called millimeters of mercury (mm Hg).

The cuff is placed around the upper arm and inflated with an air pump to a pressure that blocks the flow of blood in the main artery (brachial artery) that travels through the arm. The arm is then extended at the side of the body at the level of the heart, and the pressure of the cuff on the arm and artery is gradually released. As the pressure in the cuff decreases, a health practitioner listens with a stethoscope over the artery at the front of the elbow. The pressure at which the practitioner first hears a pulsation from the artery is the systolic pressure (the top number). As the cuff pressure decreases further, the pressure at which the pulsation finally stops is the diastolic pressure (the bottom number).

What is high blood pressure?

What is high blood pressure?

High blood pressure (HBP) or hypertension means high pressure (tension) in the arteries. Arteries are vessels that carry blood from the pumping heart to all the tissues and organs of the body. High blood pressure does not mean excessive emotional tension, although emotional tension and stress can temporarily increase blood pressure. Normal blood pressure is below 120/80; blood pressure between 120/80 and 139/89 is called "pre-hypertension", and a blood pressure of 140/90 or above is considered high.

The top number, the systolic blood pressure, corresponds to the pressure in the arteries as the heart contracts and pumps blood forward into the arteries. The bottom number, the diastolic pressure, represents the pressure in the arteries as the heart relaxes after the contraction. The diastolic pressure reflects the lowest pressure to which the arteries are exposed.

An elevation of the systolic and/or diastolic blood pressure increases the risk of developing heart (cardiac) disease, kidney (renal) disease

, hardening of the arteries (atherosclerosis or arteriosclerosis), eye damage, and stroke (brain damage). These complications of hypertension are often referred to as end-organ damage because damage to these organs is the end result of chronic (long duration) high blood pressure. For that reason, the diagnosis of high blood pressure is important so efforts can be made to normalize blood pressure and prevent complications.

It was previously thought that rises in diastolic blood pressure were a more important risk factor than systolic elevations, but it is now known that in people 50 years or older systolic hypertension represents a greater risk.

The American Heart Association estimates high blood pressure affects approximately one in three adults in the United States - 73 million people. High blood pressure is also estimated to affect about two million American teens and children, and the Journal of the American Medical Association reports that many are under-diagnosed. Hypertension is clearly a major public health problem.

What Is Jock Itch?

What Is Jock Itch?

Jock itch is a pretty common fungal infection of the groin and upper thighs. It's part of a group of fungal skin infections called tinea. The medical name for jock itch is tinea cruris (pronounced: tih-nee-uh krur-us).

Jock itch, like other tinea infections, is caused by several types of mold-like fungi called dermatophytes (pronounced: dur-mah-tuh-fites). All of us have microscopic fungi and bacteria living on our bodies, and dermatophytes are among them. Dermatophytes live on the dead tissues of your skin, hair, and nails and thrive in warm, moist areas like the insides of the thighs. So, when the groin area gets sweaty and isn't dried properly, it provides a perfect environment for the fungi to multiply and thrive.

First Aid: Wounds

DEFINITION

A wound is a break in the continuity of a tissue of the body, either internal or external. Wounds are classified as open or closed. An open wound is a break in the skin or in a mucous membrane. A closed wound involves underlying tissues without a break in the skin or a mucous membrane.

CAUSES

Wounds usually result from external physical forces. The most common causes of wounds are motor vehicle accidents, falls, and the mishandling of sharp objects, tools, machinery, and weapons.

EFFECTS

Any injury, unless it is very minor, may be harmful not only to the tissues directly involved but also to the functions of the entire body. Wounds that threaten life include those that produce cessation of breathing, severe bleeding, shock, or damage to the brain, heart, or other vital organ.

The local effects of an open or closed wound may include loss of blood, interference with blood supply, destruction of tissue, nerve injury, functional disturbances, and contamination with foreign material. These effects often involve nearby uninjured tissues. Even superficial wounds sometimes take a week or more to heal. The healing process includes absorption of blood and serum that have seeped into the area, repair of injured cells, replacement of dead cells with scar tissue, and recovery of the body from functional disturbances, if there were any.

The two most serious first aid problems caused by open wounds are a large, rapid loss of blood, which may result in shock, and contamination and infection of exposed body tissue.

TYPES AND CAUSES OF OPEN WOUNDS

Open wounds range from those that bleed severely but are relatively free from the danger of infection to those that bleed little but have greater potential for becoming infected. Often the victim has more than one type of wound.

Abrasions

An abrasion (Fig. 1) results from scraping (abrading) the skin and thereby damaging it. Bleeding in an abrasion is usually limited to oozing of blood from ruptured small veins and capillaries. However, there is a danger of contamination and infection, because dirt and bacteria may have been ground into the broken tissues.

Abrasions commonly result from falls or the handling of rough objects. Examples are skinned knees, rope burns (which are actually abrasions, not burns), and shallow multiple scratches.

Incisions

Incised wounds, or cuts (Fig. 2), in body tissues are commonly caused by knives, metal edges, broken glass, or other sharp objects. The degree of bleeding depends on the depth and extent of a cut. Deep cuts may involve blood vessels and may cause extensive bleeding. They may also damage muscles, tendons, and nerves.

Lacerations

Lacerations (Fig. 3) are jagged, irregular, or blunt breaks or tears in the soft tissues. Bleeding may be rapid and extensive. The destruction of tissue is greater in lacerations than in cuts. The deep contamination of wounds that result from accidents involving moving parts of machinery increases the chances of later infection.

Punctures

Puncture wounds (Fig. 4) are produced by bullets and pointed objects, such as pins, nails, and splinters. External bleeding is usually minor, but the puncturing object may penetrate deeply into the body and thus damage organs (as well as soft tissues) and cause severe internal bleeding. Because puncture wounds generally are not flushed out by external bleeding, they are more likely than some other wounds to become infected. Tetanus organisms and other harmful bacteria that grow rapidly in the absence of air and in the presence of warmth and moisture can be carried deep within body tissues by a penetrating object.

Avulsions

Avulsion wounds (Fig. 5) involve the forcible separation or tearing of tissue from the victim's body. Avulsions are commonly caused by animal bites and accidents involving motor vehicles, heavy machinery, guns, and explosives. They are usually followed immediately by heavy bleeding. A detached finger, toe, nosetip, ear, or, in rare cases, whole limb may be successfully reattached to a victim's body by a surgeon if the severed part is sent with the victim to the hospital.

FIRST AID FOR OPEN WOUNDS

If the wound is in an inconspicuous location, is not deep, and gapes slightly, the first-aider may find that he need only hold the wound edges together and dress and bandage the injury. At times, however, it may be difficult for the first-aider to decide whether a wound needs medical care. He may ask himself, for example, whether it will need suturing by a physician. Identified below are a number of open-wound conditions that require medical treatment after emergency care has been provided:

- Blood spurting from a wound, even if controlled initially by first aid.

- Bleeding that persists despite all efforts to control it.

- An incised wound deeper than the outer layer of skin.

- Any laceration, deep puncture, or avulsion.

- Severed or crushed nerve, tendon, or muscle.

- Laceration of the face or other parts of the body where scar tissue would be noticeable after healing.

- Skin broken by a bite, human or animal.

- Heavy contamination of a wound by soil or organic fertilizer (manure).

- Foreign object embedded deep in the tissue.

- Foreign matter in a wound, not possible to remove by washing.

- Any other open-wound situation in which there is doubt about what to do.

Severe Bleeding

Loss of more than a quart of blood is a threat to a person's survival. Hemorrhage from the aorta (the largest blood vessel of the body) or from combined external and internal injuries (such as those in a gunshot wound) may be so rapid and extensive that the victim dies almost immediately. The loss of blood in some other kinds of wounds, such as the partial or complete severing of an arm or a leg, may not cause death as quickly, but large amounts of blood can be lost, and bleeding must be controlled.

The body of a victim who is bleeding severely can make some natural adjustments that help to slow down the blood loss. Even initial severe bleeding, such as the uncontrolled hemorrhage from a cut artery, may lessen or stop spontaneously. When a large blood vessel is completely severed, the normal elasticity of muscle layers in the vessel walls tends to make the cut ends retract. This retraction reduces the size of the opening through which blood can escape, and the flow of blood may slow down enough to permit clotting to begin. However, if a blood vessel is only partially cut, it will not retract to reduce the size of the opening, and bleeding will continue unless clotting occurs or the blood pressure decreases.

Blood pressure is another natural influence on bleeding. As the pressure drops, owing to the decreased volume of blood in the vessels, bleeding from the wound tends to slow down. A lowered pressure, however, is a grave sign, and death from severe shock is possible. In the case of some wounds that would be expected to bleed severely but are producing little or no evident loss of blood, the victim may already be in an advanced degree of shock. Such wounds must be watched carefully, because rapid bleeding may begin when measures to combat shock help to restore normal blood circulation.

First-aiders are urged to remember that a relatively small amount of bleeding, such as that from an open scalp wound, can make a victim look as if he were in a critical state, even when there is no danger of death due to bleeding. However, it is logical to assume that any loss of blood is harmful to the victim, inasmuch as it could interfere with the normal functioning of his circulatory system; and, because it is possible for a person to bleed to death in a very short period, blood loss of any extent should be stopped immediately.

Three distinct techniques are recommended to stop severe bleeding: direct pressure, elevation, and pressure on the supplying artery. A fourth, technique, the use of a tourniquet, may be considered only when all other methods have failed to control severe bleeding. The four techniques are described below in order of preference.

Direct Pressure

Severe bleeding of an open wound can usually be controlled by pressing with the palm of one hand on a compress of cloth over the entire area of the wound. A thick pad of sterile gauze is preferable, but any soft, clean cloth can be used in an emergency. Even unclean material can be used, but only if nothing better is immediately available.

In an emergency, in the absence of compresses, the bare hand or fingers may be used, but only until a compress can he applied. Do not disturb blood clots that form in the cloth. If blood soaks through the entire compress, do not remove it; add more thick layers of cloth and continue direct hand pressure even more firmly. The objective is to control the hemorrhage by compressing the bleeding vessels against something more solid, such as underlying bone or uninjured tissues.

The reason for applying hand pressure directly is to prevent loss of blood from the body without interfering with normal blood circulation. The first-aider is handicapped in carrying out other emergency care, and if such care is necessary, the compress should be secured in place by a pressure bandage. To apply the pressure bandage, place and keep the center of the bandage or strip of cloth directly over the pad on the wound; maintain a steady pull on the bandage to keep the pad firmly in place as you wrap the ends of it around the body part. Tie the bandage with a knot directly over the pad.

Elevation

Unless there is evidence of a fracture, a severely bleeding open wound of the head, neck, arm, or leg should be elevated—that is, raised above the level of the victim's heart. Elevation uses the force of gravity to help reduce the blood pressure in the injured area and thus aids in slowing down the loss of blood through the wound opening. However, direct pressure on a thick pad over the wound must be continued.

Pressure on the Supplying Artery

If direct pressure and elevation do not stop severe bleeding from an open wound of the arm or leg, the pressure point technique may be required. This technique involves applying pressure at a specific point on the arm or leg to temporarily compress the main artery supplying blood to the affected limb. There is one recommended pressure point on each arm and leg.

The use of a pressure point not only stops blood circulation to the injured limb but also stops circulation within the limb. Therefore, pressure points should not be used unless the technique is absolutely necessary to help stop severe bleeding. If the use of a pressure point is necessary, do not substitute the technique for direct pressure and elevation but use it in addition to those techniques. You may need some help to apply all three control methods at the same time. As a rule, do not use a pressure point in conjunction with direct pressure and elevation any longer than is necessary to stop the bleeding, but be prepared to reapply pressure at the pressure point if bleeding recurs.

For a severely bleeding open arm wound, apply pressure over the brachial artery, forcing the artery against the arm bone. This pressure point is on the inside of the arm in the groove between the large muscle masses (biceps and triceps) about midway between the armpit and the elbow. To apply pressure on the brachial artery, grasp the middle of the victim's upper arm with your thumb on the outside of his arm and your other fingers on the inside. Press your other fingers toward your thumb to create an inward force from opposite sides of the arm. Use the fiat inside surface of your fingers, not your fingertips. This pressure inward holds and closes the artery by compressing it against the arm bone.

For severe bleeding from an open leg wound, apply pressure on the femoral artery, forcing it against the pelvic bone. This pressure point is on the front of the thigh just below the middle of the crease of the groin where the artery crosses over the pelvic bone on its way to the leg. To apply pressure on the femoral artery, quickly place the victim on his back and put the heel of your hand directly over the pressure point. Then lean forward over your straightened arm to apply pressure against the underlying bone. Apply pressure as needed to close the artery. Keep your arm straight to prevent arm tension and muscular strain. If bleeding is not controlled, it may be necessary to compress directly over the artery with the flat of the fingertips and to apply additional pressure over the fingertips with the heel of the other hand.

Tourniquet

A tourniquet is a wide band of cloth or other material placed just above a wound to stop all flow of blood. Do not use a narrow band, rope, or wire. Application of a tourniquet can control severe bleeding from an open wound of the arm or leg but is rarely needed and should not be used except in a critical emergency where direct pressure on the appropriate pressure point fails to stop bleeding. The use of a tourniquet is dangerous. Properly applied, the tourniquet will stop all blood circulation to a limb beyond the point of application. But if it is left in place for an extended period, uninjured tissues may die from lack of blood and oxygen. Releasing the tourniquet tends to increase the danger of shock, and bleeding may resume. If a tourniquet is improperly applied (too loosely), it will not stop arterial blood flow to the affected limb, but will only slow or stop venous blood flow from the limb. The result is increased, instead of controlled, bleeding from the wound. The decision to apply a tourniquet is in reality a decision to risk sacrifice of a limb in order to save a Life. Once a tourniquet is applied, care by a physician is imperative.

To apply a tourniquet, place it just above the wound. Do not allow it to touch the wound edges. If the wound is in a joint area or just below, place the tourniquet immediately above the joint.

- Wrap the tourniquet band twice tightly around the limb and tie an overhand knot (Fig. 16A).

- Place a short, strong stick—or similar article that will not break—on the overhand knot; tie two additional overhand knots on top of the stick (Fig. 16B).

- Twist the stick to tighten the tourniquet until bleeding stops (Fig. 16C).

- Secure the stick in place with the loose ends of the tourniquet (Fig. 16D), a strip of cloth, or other improvised material (Fig. 16E).

- Make a written note of the location of the tourniquet and the time it was applied and attach the note to the victim's clothing.

- Treat the victim for shock and give necessary first aid for other injuries.

- Do not cover a tourniquet.

Once the tourniquet has been applied, it should not be loosened except on the advice of a physician.

Prevention of Contamination and Infection

Open wounds are subject to contamination and infection. The danger of infection can be prevented or lessened by taking the appropriate first aid measures, depending on the severity of bleeding. Once a compress has been applied to control bleeding, whether bleeding has been severe or not, do not remove or disturb the cloth pressure pad initially placed on the wound. Do not attempt to cleanse the wound. The victim must have medical care, and cleansing the wound may cause resumption of bleeding.

A wound that is not bleeding severely and that does not involve tissues deeper than the skin should be cleansed thoroughly to remove contamination before it is dressed and bandaged, especially if medical attention will be delayed. Do not remove foreign materials from muscle or other deep tissues; such removal should be carried out only by a physician. To cleanse a wound that does not involve tissues deeper than the skin, wash your own hands thoroughly with ordinary hand soap or mild hand detergent. Wash in and around the victim's wound to remove bacteria and other foreign matter. Rinse the wound thoroughly by flushing with clean water, preferably running tap water. Blot the wound dry with a sterile gauze pad or clean cloth. Apply a dry sterile or clean dressing and bandage it firmly in place.

Caution the victim to see his physician promptly if evidence of infection appears (see page 40).

Removing Foreign Objects

In small open wounds, wood splinters and glass fragments often remain in the surface tissues or in tissues just beneath the surface. As a rule, such objects only irritate the victim; they do not usually incapacitate a person or cause systemic body infection. However, they can cause infection if they are not removed. Use tweezers sterilized over a flame or in boiling water to pull out any foreign matter from the surface tissues. Objects embedded just beneath the skin can be lifted out with the tip of a needle that has been sterilized in rubbing alcohol or in the heat of a flame. Foreign objects, regardless of size, that are embedded deeper in the tissues should be left for removal by a physician.

The fishhook is probably one of the more common types of foreign objects that may penetrate the skin. Often, only the point of the hook enters, not penetrating deeply enough to allow the barb to become effective; in this case, the hook can be removed easily by backing it out. If the fishhook goes deeper and the barb becomes embedded (Fig. 17), the wisest course is to have a physician remove it. If medical aid is not available, remove the hook by pushing it through (Fig. 18) until the barb protrudes. Using a cutting tool, cut the hook either at the barb or at the shank and remove it. Cleanse the wound thoroughly and cover it with an adhesive compress. A physician should be consulted as soon as possible because of the possibility of infection, especially tetanus.

Some penetrating foreign objects, such as sticks and pieces of metal, may protrude loosely from the body or even be fixed, such as a stake in the ground or a wooden spike or metal rod of a fence on which the victim has become impaled. Under no circumstances should the victim be pulled loose from such an object. Obtain help at once, preferably from ambulance or rescue personnel, who are equipped to handle the problem. Support the victim and the object to prevent movements that could cause further damage. If the object is fixed or protrudes more than a few inches from the body, it should be held carefully to avoid further damage, cut off at a distance from the skin, and left in place. To prevent further injury during transport of the victim, immobilize the protruding end with massive dressings. The victim should then be taken to the hospital without delay.

Dressing the Wound

A dressing is a cover placed over a wound to protect it from additional injury and contamination and to assist in the control of bleeding. Bandaging a wound holds the dressing in place, assists in control of bleeding, offers support, and promotes restraint of movement. For detailed instruction on the application of dressings and bandages, see chapter 14.

INFECTION

The period of healing after an injury may be greatly prolonged by infection, which is the result of invasion and growth of bacteria within the tissues of the body. Bacteria are normally present in large numbers on the skin, in the nose, in the mouth, in the upper air passages, in the digestive tract, on hair, in hair follicles, in discharges from the body, in the air, and in soil. Serious infection may develop within hours or days after an injury, when bacteria get inside the tissues of the body through breaks in the skin or mucous membranes, even if the injury seems insignificant.

Careful cleansing of an open wound removes particles of dead tissue and foreign matter and reduces the number of bacteria, thereby helping to prevent infection. Bacteria tend to multiply rapidly in devitalized tissues; one reason is that white cells and other blood elements that ordinarily combat infection by destroying bacteria or by neutralizing bacterial products cannot reach dead tissues.

The threat of tetanus infection (lockjaw) must never be overlooked. A current immunization record will assist the physician in determining whether a tetanus injection or a tetanus toxoid booster injection should be given. Tetanus infection is so serious that a penetrating wound of any kind that involves tissues deeper than the skin should be seen by a physician as soon as possible.

Symptoms

Even if measures are taken to prevent contamination in a wound, infection may still develop. An infected wound can be recognized by the presence of any of the following symptoms:

- Swelling of the affected part.

- Redness of the affected part.

- A sensation of heat.

- Throbbing pain.

- Tenderness.

- Fever.

- Evidence of pus, either collected beneath the skin or draining from the wound.

- Swollen lymph glands ("kernels") in the groin (leg infection), in the armpit (arm infection), or in the neck (infection of the head).

- Red streaks leading from the wound—an indication that the infection is spreading through the lymphatic circulation channels.

Interim Emergency Care

Infected wounds require prompt medical care, but if a long delay is necessary before the victim can be treated by a physician, the following temporary steps should be taken:

- Immobilize the entire infected area and keep the victim lying down, preferably in bed, to reduce physical activity that would spread the infection.

- Elevate the affected body part, if possible. Elevation is especially important for infected wounds of the head, hands, legs, and feet.

- Apply heat to the area with hot water bottles, or put warm, moist towels or cloths over the wound dressing. Change the wet packs often enough to keep them warm and cover them with a dry towel wrapped in plastic, aluminum foil, or waxed paper to hold in the warmth and to protect bedclothing.

- Continue applying the warm packs for 30 minutes; then remove them and cover the wound with a sterile dressing for another 30 minutes. Apply the warm packs again. Repeat the whole process until medical care or advice can be obtained.

- If a physician is reached by telephone, be prepared to give him information about the victim's temperature and the general appearance of the wound.

Remember—the above directions are for interim care only; do not delay efforts to get medical care for the victim.

BITES

Injuries produced by animal or human bites may cause punctures, lacerations, or avulsions. Not only is care needed for open wounds but also consideration must be given to the dangers of infection, especially rabies.

Human

All human bites that break the skin may become seriously infected, because the mouth is heavily contaminated with bacteria. Cleanse the wound thoroughly, cover it, and seek medical attention.

Animal

The bite of any animal, whether it is a wild animal or a pet, may result in an open wound. Dog and cat bites are common. Although a dog bite is likely to cause more extensive tissue damage than a cat bite, the cat bite may be more dangerous, because a wider variety of bacteria is usually present in the mouth of a cat. Many wild animals, especially bats, raccoons, and rats, transmit rabies. Tetanus is an added danger in animal bites. Any animal bite carries a great risk of infection.

Rabies, or hydrophobia, is an infectious disease due to a virus. It can be transmitted through the infected saliva of a rabid animal to another animal or to a human being. The infection can be spread when the rabid animal's bite causes an open wound, even a scratch, or when the rabid animal licks an existing open wound on a human or a nonrabid animal.

The indications that an animal is rabid are variable and may be misleading. On the one hand, a rabid animal may drool, be irritable, be unusually active, or be clearly dangerous; on the other hand, it may be quiet, partially paralyzed, stuporous, or even affectionate. Every effort must be made to restrain any suspected rabid animal so that it can be kept under observation to see whether it develops the final stages of the disease. Do not kill such an animal unless it is absolutely necessary. If killing is necessary, take precautions not to damage the animal's head, which must be examined by public health authorities. Get help and advice from the police, a veterinarian, a physician, or local public health authorities as to how long a live animal that is thought to be rabid should be observed. Regulations vary from one community to another, but the average period is 15 days. If the animal cannot be caught for observation, arrange for immediate rabies immunization for any person it has bitten.

An animal in the final stages of rabies will develop some of the signs of the disease within 48 hours and will usually die within a few days after those signs appear. If the animal proves to be rabid, vaccine therapy must be given to build up body immunity in the victim in time to prevent the disease.

There is no known cure for rabies once its final-stage symptoms develop. After a person is bitten and the rabies virus is transmitted to him, the virus must go through an incubation period that may vary in duration. Any person who is bitten by an animal thought to be rabid should take no chances and should get medical care immediately. In the meantime, before a physician takes charge, thoroughly wash the wound with soap and water, flush it liberally, and apply a dressing. Movement of the arms and legs should be avoided until the victim has had medical care.

CLOSED WOUNDS

Most closed wounds are caused by external forces, such as falls and motor vehicle accidents. Many closed wounds are relatively small and involve soft tissues; the black eye is an example. Others, however, involve fractures of the limbs, spine, or skull and damage to vital organs (see page 44, Fig. 19) within the skull, chest, or abdomen. Massive injury to soft tissues—such as muscles, blood vessels, and nerves—can be very serious and can result in lasting disabilities.

Signs and Symptoms

Pain and tenderness are the most common symptoms of a closed wound. Usual signs are swelling and discoloration of soft tissues and deformity of limbs caused by fractures or dislocations. Suspect a closed wound with internal bleeding and possible rupture of a body organ whenever powerful force exerted on the body has produced severe shock or unconsciousness. Even if signs of injury are obvious, internal injury is probable when any of the following general symptoms are present:

- Cold, clammy, pale skin, very rapid but weak pulse, rapid breathing, and dizziness.

- Pain and tenderness in a part of the body in which injury is suspected, especially if deep pain continues but seems out of proportion to the outward signs of injury.

- Uncontrolled restlessness and excessive thirst.

- Vomiting or coughing up of blood or passage of blood in the urine or feces.

Emergency Care

Carefully examine the victim for fractures and other injuries to the head, neck, chest, abdomen, limbs, back, and spine. If an internal injury is suspected, get medical care for the victim as soon as possible. If a closed fracture is suspected, immobilize the affected area before moving the victim. Carefully transport him in a lying position and give special attention to preventing shock. Also, watch the victim's breathing and take measures to prevent either blockage of the airway or stoppage of breathing. Do not give fluids by mouth to a victim suspected of having internal injury, regardless of how much he complains of thirst.

When a relatively small closed wound occurs (such as a black eye), put cold applications on the injured area. The applications will help to reduce additional swelling and may slow down internal bleeding.

Breathing Problems - Natural Solutions

Breathing difficulties can seriously handicap our ability to function and enjoy life. Air is our most vital source of energy and vitality. When we suffer from asthma, bronchitis, allergies, frequent colds or simply insufficient oxygen intake, we are prone to a lack of energy, vitality and /or mental clarity.

Every cell within our body depends on an abundant supply of oxygen for proper metabolism and vitality.

Some Causes of Breathing Problems

1. Hereditary weakness may make our lungs or other organs of respiratory apparatus weak points in our system. Thus when tired, overworked, anxious or stressed, these parts of the body will start to malfunction. This does not mean, however, that we must suffer. It is in our hands to live in a certain way so as nurture and protect our bodies and minds. Among such weaknesses we should include the inability of the immune system to effectively protect the body from microbes and viruses. In some cases the immune system may work overtime trying to protect the body from "imagined" dangers. Allergies and asthma are often the result of such over-reactions from the immune system.

2. Environmental factors may also aggravate the condition. Cold and humid weather tend to accentuate breathing problems. Pollen and other particles in the air may cause allergic reactions. Occupational conditions such as working in a dusty area or in a smoke filled room may also aggravate the problem. Pollution irritates our nasal passage and lungs. Smoking cigarettes obviously damages our lungs, cutting off our supply of oxygen.

3. An over production of mucus clogs up the breathing passages, obstructing breathing. Foods, which tend to cause excess mucus, are all dairy products, white flour, white rice and sweets.

4. A lack of sufficient liquid intake causes the mucus to thicken and cling to the lungs and other breathing passages. This creates a favorable environment for microbes to reproduce.

5. Blockages in the spinal vertebrae or tension in the muscles of the upper back may also obstruct the flow of nerve impulses and bioenergy to the lungs. This may inhibit the proper functioning of the lungs.

6. Emotional blockages are directly connected with our breathing. People, who experience anxiety, depression, fear, nervous tension or a poor self-image, tend to subconsciously hold their breath. Thus their breathing is tense, shallow, and sometimes spasmodic.

Long-term emotional blockages may also affect the adrenal glands and thus hormonal disorders may also play their part in the problem. Negative emotions also depress or disturb the functioning of the immune system.

7. A lack of proper education in breathing is another reason why people suffer from breathing problems. It is entirely possible for us to learn to use our lungs more effectively for greater energy, vitality, peace and clarity of mind. This should be learned from an experienced breath coach.

Some Solutions

1. Environmental & Habitual Factors

a. Surround yourself with large green leafed plants, which produce oxygen and absorb pollution.

b. Get out of the city frequently. Go the sea or mountains and breathe fresh clean air.

c. Use regular deep breathing to clean out and rejuvenate your lungs.

d. Deep breathing while walking can clean out a considerable amount of pollution from the lungs.

e. If you smoke, then - love yourself - and stop.

2. Dietary Guidelines

a. Avoid all diary products, white sugar, sweets, white flour and white rice. When the problem has subsided, then we can start taking small quantities of dairy products while watching the body's reaction.

b. Eat plenty of fruits and vegetables.

c. Drink plenty (6 or 8 cups per day) of warm liquid daily. This may be water, herb teas, or water with lemon. Do not drink refrigerated or iced drinks.

d. When one has a cold, an onion and garlic soup spiced with pepper, cinnamon ginger and cloves, opens up the nasal passages and allows the congestion to flow out.

e. In some cases the use of natural vitamin C tablets can be helpful.

3. Facing emotional factors is essential for healing the cause of the breathing problems.

There are various ways in which we can find relief from these emotional factors and then eventually analyze them and transcend them.

a. Self-analysis or objective-self observation can free us from various emotional attachments and fears.

b. Positive thinking, affirmations, and positive thought projection can neutralize negative emotions and tendencies.

c. Various Body-centered catharsis techniques in addition to reprogramming techniques such as EMDR, TFT and EFT can free us from emotional based psychosomatic symptoms.

4. Exercises and Techniques

A. With the help of various exercises and techniques we seek to:

1. Remove the blockages and tensions from the upper back and chest area.

2. Develop greater freedom and control over the muscles of breathing.

3. Bring blood and healing energies to the chest area.

4. Open up the nasal passages if they are blocked.

5. Stimulate the harmonious functioning of the adrenal glands and immune system.

B. Techniques will need the guidance of an experienced coach are:

1. To start with we can simply practice deep breathing exercises. These exercises will give us relief from tension and may even bring the cause for our emotional tension to the surface so that we may see it more clearly and objectively.

2. Exercises for the upper back and chest can also bring considerable relief from emotional tensions.

3. Deep relaxation techniques are also very effective for relaxing the whole system so that the muscles of breathing may function more freely.

4. In guided deep relaxation sessions the source of the emotional blockages can be researched through regression.

What Is Caffeine?

What Is Caffeine?

Caffeine is a drug that is naturally produced in the leaves and seeds of many plants. It's also produced artificially and added to certain foods. Caffeine is defined as a drug because it stimulates the central nervous system, causing increased alertness. Caffeine gives most people a temporary energy boost and elevates mood.

Caffeine is in tea, coffee, chocolate, many soft drinks, and pain relievers and other over-the-counter medications. In its natural form, caffeine tastes very bitter. But most caffeinated drinks have gone through enough processing to camouflage the bitter taste.

Teens usually get most of their caffeine from soft drinks and energy drinks. (In addition to caffeine, these also can have added sugar and artificial flavors.) Caffeine is not stored in the body, but you may feel its effects for up to 6 hours.

Overcoming Social Phobia

Overcoming Social Phobia

Dealing with social phobia takes patience, courage to face fears and try new things, and the willingness to practice. It takes a commitment to go forward rather than back away when feeling shy.

Little by little, someone who decides to deal with extreme shyness can learn to be more comfortable. Each small step forward helps build enough confidence to take the next small step. As shyness and fears begin to melt, confidence and positive feelings build. Pretty soon, the person is thinking less about what might feel uncomfortable and more about what might be fun.

Dealing With Social Phobia

Dealing With Social Phobia

People with social phobia can learn to manage fear, develop confidence and coping skills, and stop avoiding things that make them anxious. But it's not always easy. Overcoming social phobia means getting up the courage it takes to go beyond what's comfortable, little by little.

Here's who can support and guide people in overcoming social phobia:

- Therapists can help people recognize the physical sensations caused by fight–flight and teach them to interpret these sensations more accurately. Therapists can help people create a plan for facing social fears one by one, and help them build the skills and confidence to do it. This includes practicing new behaviors. Sometimes, but not always, medications that reduce anxiety are used as part of the treatment for social phobia.

- Family or friends are especially important for people who are dealing with social phobia. The right support from a few key people can help those with social phobia gather the courage to go outside their comfort zone and try something new.

Putdowns, lectures, criticisms, and demands to change don't help — and just make a person feel bad. Having social phobia isn't a person's fault and isn't something anyone chooses. Instead, friends and family can encourage people with social phobia to pick a small goal to aim for, remind them to go for it, and be there when they might feel discouraged. Good friends and family are there to celebrate each small success along the way.

Why Do Some People Develop Social Phobia?

Why Do Some People Develop Social Phobia?

Kids, teens, and adults can have social phobia. Most of the time, it starts when a person is young. Like other anxiety-based problems, social phobia develops because of a combination of three factors:

- A person's biological makeup. Social phobia could be partly due to the genes and temperament a person inherits. Inherited genetic traits from parents and other relatives can influence how the brain senses and regulates anxiety, shyness, nervousness, and stress reactions. Likewise, some people are born with a shy temperament and tend to be cautious and sensitive in new situations and prefer what's familiar. Most people who develop social phobia have always had a shy temperament.

Not everyone with a shy temperament develops social phobia (in fact, most don't). It's the same with genes. But people who inherit these traits do have an increased chance of developing social phobia. -

Behaviors learned from role models (especially parents). A person's naturally shy temperament can be influenced by what he or she learns from role models. If parents or others react by overprotecting a child who is shy, the child won't have a chance to get used to new situations and new people. Over time, shyness can build into social phobia.

Shy parents might also unintentionally set an example by avoiding certain social interactions. A shy child who watches this learns that socializing is uncomfortable, distressing, and something to avoid. - Life events and experiences. If people born with a cautious nature have stressful experiences, it can make them even more cautious and shy. Feeing pressured to interact in ways they don't feel ready for, being criticized or humiliated, or having other fears and worries can make it more likely for a shy or fearful person to develop social anxiety.

People who constantly receive critical or disapproving reactions may grow to expect that others will judge them negatively. Being teased or bullied will make people who are already shy likely to retreat into their shells even more. They'll be scared of making a mistake or disappointing someone, and will be more sensitive to criticism.

The good news is that the effect of these negative experiences can be turned around with some focused slow-but-steady effort. Fear can be learned. And it can also be unlearned, too.

Selective Mutism

Selective Mutism

Some kids and teens are so extremely shy and so fearful about talking to others, that they don't speak at all to certain people (such as a teacher or students they don't know) or in certain places (like at someone else's house). This form of social phobia is sometimes called selective mutism.

People with selective mutism can talk. They have completely normal conversations with the people they're comfortable with or in certain places. But other situations cause them such extreme anxiety that they may not be able to bring themselves to talk at all.

Some people might mistake their silence for a stuck-up attitude or rudeness. But with selective mutism and social phobia, silence stems from feeling uncomfortable and afraid, not from being uncooperative, disrespectful, or rude.

How Social Phobia Can Affect Someone's Life

How Social Phobia Can Affect Someone's Life

With social phobia, thoughts and fears about what others think get exaggerated in someone's mind. The person starts to focus on the embarrassing things that could happen, instead of the good things. This makes a situation seem much worse than it is, and influences a person to avoid it.

Some of the ways social phobia can affect someone's life include:

- Feeling lonely or disappointed over missed opportunities for friendship and fun. Social phobia might prevent someone from chatting with friends in the lunchroom, joining an after-school club, going to a party, or asking someone on a date.

- Not getting the most out of school. Social phobia might keep a person from volunteering an answer in class, reading aloud, or giving a presentation. Someone with social phobia might feel too nervous to ask a question in class or go to a teacher for help.

- Missing a chance to share their talents and learn new skills. Social phobia might prevent someone from auditioning for the school play, being in the talent show, trying out for a team, or joining in a service project. Social phobia not only prevents people from trying new things. It also prevents them from making the normal, everyday mistakes that help people improve their skills still further.

What Are People With Social Phobia Afraid Of?

What Are People With Social Phobia Afraid Of?

With social phobia, a person's fears and concerns are focused on their social performance — whether it's a major class presentation or small talk at the lockers.

People with social phobia tend to feel self-conscious and uncomfortable about being noticed or judged by others. They're more sensitive to fears that they'll be embarrassed, look foolish, make a mistake, or be criticized or laughed at. No one wants to experience these things. But most people don't really spend much time worrying about it.

The Fear Reaction

The Fear Reaction

Like other phobias, social phobia is a fear reaction to something that isn't actually dangerous — although the body and mind react as if the danger is real. This means that the person feels physical sensations of fear, like a faster heartbeat and breathing. These are part of the body's fight–flight response. They're caused by a rush of adrenaline and other chemicals that prepare the body to either fight or make a quick getaway.

This biological mechanism kicks in when we feel afraid. It's a built-in nervous system response that alerts people to danger so they can protect themselves. With social phobia, this response gets activated too frequently, too strongly, and in situations where it's out of place. Because the physical sensations that go with the response are real — and sometimes quite strong — the danger seems real, too. So the person will react by freezing up, and will feel unable to interact.

As the body experiences these physical sensations, the mind goes through emotions like feeling afraid or nervous.

People with social phobia tend to interpret these sensations and emotions in a way that leads them to avoid the situation ("Uh-oh, my heart's pounding, this must be dangerous — I'd better not do it!"). Someone else might interpret the same physical sensations of nervousness a different way ("OK, that's just my heart beating fast. It's me getting nervous because it's almost my turn to speak. It happens every time. No big deal.")

What Is Social Phobia?

What Is Social Phobia?

Social phobia (also sometimes called social anxiety) is a type of anxiety problem. Extreme feelings of shyness and self-consciousness build into a powerful fear. As a result, a person feels uncomfortable participating in everyday social situations.

People with social phobia can usually interact easily with family and a few close friends. But meeting new people, talking in a group, or speaking in public can cause their extreme shyness to kick in.

With social phobia, a person's extreme shyness, self-consciousness, and fears of embarrassment get in the way of life. Instead of enjoying social activities, people with social phobia might dread them — and avoid some of them altogether.

More Strategies That Work

More Strategies That Work

Set a quit date. Pick a day that you'll stop smoking. Tell your friends (and your family, if they know you smoke) that you're going to quit smoking on that day. Just think of that day as a dividing line between the smoking you and the new and improved nonsmoker you'll become. Mark it on your calendar.

Throw away your cigarettes — all of your cigarettes. People can't stop smoking with cigarettes still around to tempt them. Even toss out that emergency pack you have stashed in the secret pocket of your backpack. Get rid of your ashtrays and lighters, too.

Wash all your clothes. Get rid of the smell of cigarettes as much as you can by washing all your clothes and having your coats or sweaters dry-cleaned. If you smoked in your car, clean that out, too.

Think about your triggers. You're probably aware of the situations when you tend to smoke, such as after meals, when you're at your best friend's house, while drinking coffee, or as you're driving. These situations are your triggers for smoking — it feels automatic to have a cigarette when you're in them. Once you've figured out your triggers, try these tips:

- Avoid these situations. For example, if you smoke when you drive, get a ride to school, walk, or take the bus for a few weeks. If you normally smoke after meals, make it a point to do something else after you eat, like read or call a friend.

- Change the place. If you and your friends usually smoke in restaurants or get takeout and eat in the car, suggest that you sit in the no-smoking section the next time you go out to eat.

- Substitute something else for cigarettes. It can be hard to get used to not holding something and having something in your mouth. If you have this problem, stock up on carrot sticks, sugar-free gum, mints, toothpicks, or even lollipops.

The Difficulty in Kicking the Habit

The Difficulty in Kicking the Habit

Smokers may have started smoking because their friends did or because it seemed cool. But they keep on smoking because they became addicted to nicotine, one of the chemicals in cigarettes and smokeless tobacco.

Nicotine is both a stimulant and a depressant. That means it increases the heart rate at first and makes people feel more alert (like caffeine, another stimulant). Then it causes depression and fatigue. The depression and fatigue — and the drug withdrawal from nicotine — make people crave another cigarette to perk up again. According to many experts, the nicotine in tobacco is as addictive as cocaine or heroin.

But don't be discouraged; millions of Americans have permanently quit smoking. These strategies can help you quit, too:

Put it in writing. People who want to make a change often are more successful when they put it in writing. So write down all the reasons why you want to quit smoking, such as the money you will save or the stamina you'll gain for playing sports. Keep that list where you can see it, and add to it as you think of new reasons.

Get support. People whose friends and family help them quit are much more likely to succeed. If you don't want to tell your parents or family that you smoke, make sure your friends know, and consider confiding in a counselor or other adult you trust. And if you're having a hard time finding people to support you (if, say, all your friends smoke and none of them is interested in quitting), you might consider joining a support group, either in person or online.

Preventing a Migraine

Preventing a Migraine

The best way to prevent migraines is to learn what triggers (sets off) your migraines and then try to avoid these triggers. Take a break from activities that provoke a migraine, such as using the computer for a long time. If you know that certain foods trigger your migraines, try to avoid them. Some people find that cutting back on caffeine intake or drinking a lot of water can help prevent migraines.

Make a plan for all the things you have to do — especially during stressful times like final exams — so you don't feel overwhelmed when things pile up. Regular exercise can also reduce stress and make you feel better. If your doctor has prescribed medication, always have a dose on hand. Then if you feel a migraine coming, take your medicine. You can also try lying down in a quiet, dark room until the pain starts to go away.

Because migraines are so different for different people, it helps to keep a headache diary and get to know what provokes migraines in your own case. The more you understand your headaches, the better prepared you can be to fight them.

How Do Doctors Diagnose and Treat Migraines?

How Do Doctors Diagnose and Treat Migraines?

Because migraine headaches are different in different people — in some people, for example, they are triggered by hormones; in others, stress and lifestyle influence headaches — how doctors treat someone depends on the type of migraine that person gets.

A doctor may ask someone having migraines to keep a headache diary to help figure out what triggers the headaches. If your doctor has asked you to keep such a diary, the information you record will help the doctor figure out the best treatment. A doctor may also take blood tests or imaging tests, such as a CAT scan or MRI of the brain, to rule out medical problems that might cause a person's migraines.

Part of treatment may involve making certain changes in your lifestyle — like changing your sleep patterns or dietary habits or avoiding certain stressors that trigger your migraines. Your doctor may also start you on a pain relief medication or also prescribe medicines that help with nausea and vomiting. Some people need preventive medicines that are taken every day to reduce the number and severity of the migraines.

Some doctors teach a technique called biofeedback to their patients with migraines. This technique helps a person learn to relax and use the brain to gain control over certain body functions (like heart rate and muscle stress) that cause tension and pain. If a migraine begins slowly, many people can use biofeedback to remain calm and stop the attack.

There have also been studies indicating that some alternative methods, such as acupuncture and the use of certain herbs, can help some people. However, it is important to ask your physician about alternative medicines before trying them for yourself. This is especially true of herbal treatments because they can interfere with more traditional methods of treatment.

What's a Migraine Attack Like?

What's a Migraine Attack Like?

Most migraines last from 30 minutes to 6 hours; some can last a couple of days.

Every migraine begins differently. Some people just don't feel right. Light, smell, or sound may bother them or make them feel worse. Sometimes, if they try to continue with their usual routine after the migraine starts, they may become nauseated and vomit. Often the pain begins only on one side of the head. Trying to perform physical activities may worsen the pain.

Some people get auras, a kind of warning that a migraine is on the way. The most common auras include blurred vision and seeing spots, colored balls, jagged lines, or bright or flashing lights or smelling a certain odor. The auras may only be seen in one eye. An aura usually starts about 10 to 30 minutes before the start of a migraine. Some individuals experience a migraine premonition hours to days prior to the actual headache. This is slightly different from auras and may cause cravings for different foods, thirst, irritability, or feelings of intense energy.

Some people with migraines also have muscle weakness, lose their sense of coordination, stumble, or even have trouble talking either just before or while they have a headache.

What Makes a Headache a Migraine?

What Makes a Headache a Migraine?

Almost everyone gets headaches. You might feel throbbing in the front of your head during a cold or bout with the flu, for example. Or you might feel pain in your temples or at the back of your head from a tension headache after a busy day. Most regular headaches produce a dull pain around the front, top, and sides of your head, almost like someone stretched a rubber band around it.

A migraine is different. Doctors define it as a recurrent headache that has additional symptoms. The pain is often throbbing and on one or both sides of the head. People with migraines often feel dizzy or sick to their stomachs. They may be sensitive to light, noise, or smells. Migraines can be disabling, and teens with migraines often need to skip school, sports, work, or other activities until they feel better.

If you have migraines, you are not alone. Experts estimate that up to 10% of teens and young adults in the United States get migraines. Before age 10, an equal number of boys and girls get migraines. But after age 12, during and after puberty, migraines affect girls three times more often than boys.